Forensic Anthropology

Please don’t read this section if you’re squeamish.I give a lot of people the elevator pitch of my experience in Forensic Anthropology. This is the (very) long version.

Below is a non-comprehensive account of my experience with Forensic Anthropology including my foray into Forensic Facial Reconstruction and the time I worked at the Body Farm.

Below is a non-comprehensive account of my experience with Forensic Anthropology including my foray into Forensic Facial Reconstruction and the time I worked at the Body Farm.

THIS IS WHY I’M OBSESSED WITH SKULLS

Forensic Facial Reconstruction is a lot of science and a lot of artistic instinct.

A quick intro to the process: Every skull has certain variables and measurements that indicate what a person’s face looked like while they were alive. Kind of. No skull will tell you what color a person’s eyes were, whether or not they broke their nose, how plump their face was etc. etc. There’s a lot of guestimating involved. It requires the reconstruct-er to take a bit of “artistic liberty”, and make some informed guestimation.

It’s kind of like being god, except “god” created the living and I wanted to recreate the dead.

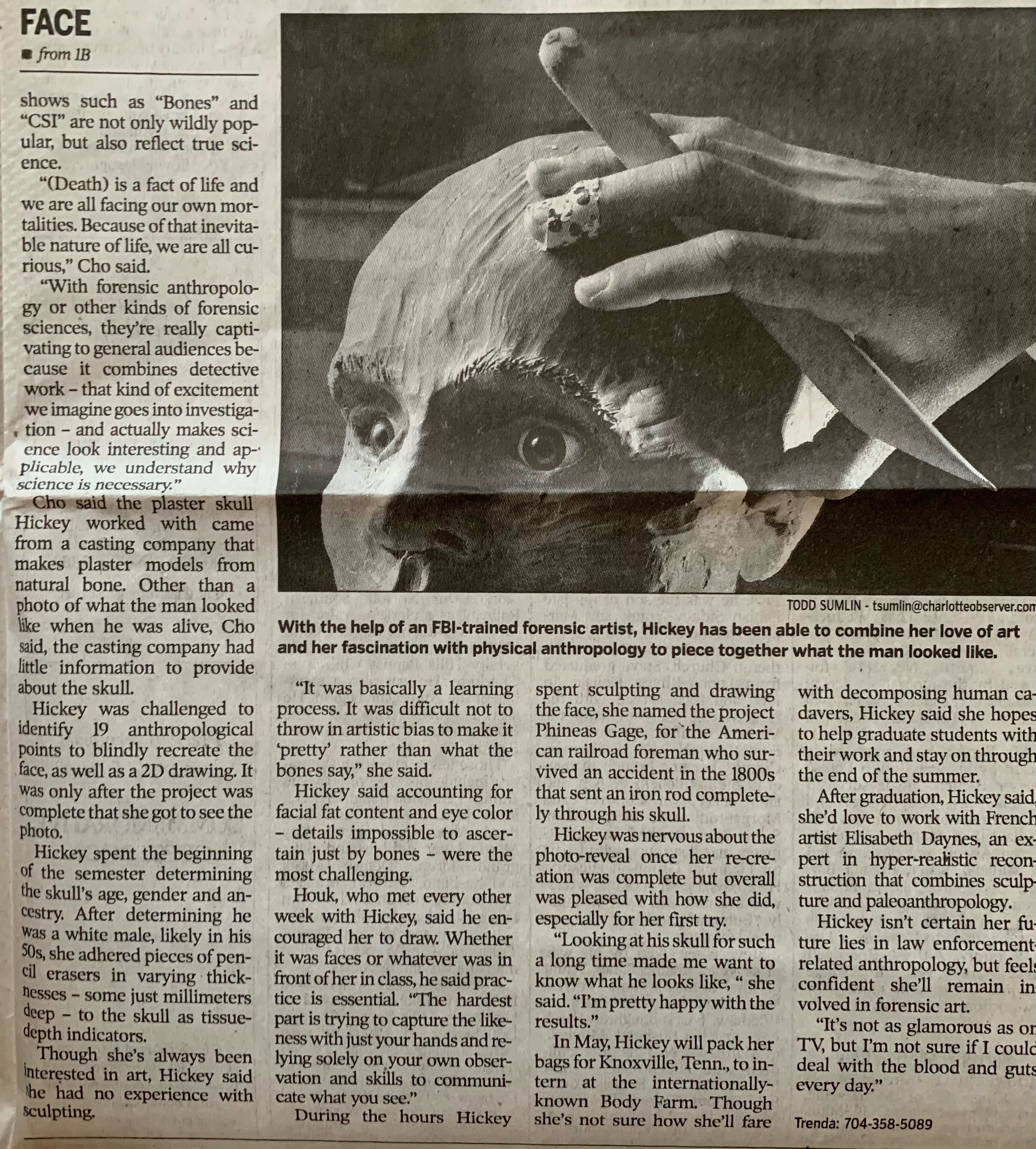

Here’s an article from the Charlotte Observer that details the whole project a bit more.

Forensic Facial Reconstruction is a lot of science and a lot of artistic instinct.

A quick intro to the process: Every skull has certain variables and measurements that indicate what a person’s face looked like while they were alive. Kind of. No skull will tell you what color a person’s eyes were, whether or not they broke their nose, how plump their face was etc. etc. There’s a lot of guestimating involved. It requires the reconstruct-er to take a bit of “artistic liberty”, and make some informed guestimation.

It’s kind of like being god, except “god” created the living and I wanted to recreate the dead.

Here’s an article from the Charlotte Observer that details the whole project a bit more.

KEY THINGS TO NOTE

I shadowed an FBI trained Forensic Artist who helped me learn the 2D part of this process and showed me the ins and outs of Criminal Sketch Artistry.

I learned how to use ForDisc which is a program that somewhat accurately predicts distance between skeletal markers and flesh (i.e. skin depth) on the skull with a very high degree of variability. This required me to also learn how to accurately measure the different features of a skull.

I taught my self how to sculpt and had never worked with clay before this.

I actually successfully reconstructed a man’s face using a plaster mold of a skull with a high level of accuracy.

I named my new friend Phineas Gage.

I for some reason was wearing a Mickey Mouse Band-Aid when the above photos were taken.

I shadowed an FBI trained Forensic Artist who helped me learn the 2D part of this process and showed me the ins and outs of Criminal Sketch Artistry.

I learned how to use ForDisc which is a program that somewhat accurately predicts distance between skeletal markers and flesh (i.e. skin depth) on the skull with a very high degree of variability. This required me to also learn how to accurately measure the different features of a skull.

I taught my self how to sculpt and had never worked with clay before this.

I actually successfully reconstructed a man’s face using a plaster mold of a skull with a high level of accuracy.

I named my new friend Phineas Gage.

I for some reason was wearing a Mickey Mouse Band-Aid when the above photos were taken.

THIS IS THE SECTION WHERE I TALK ABOUT THE BODY FARM

The first thing you notice is the smell.

In the summer of 2013 I worked at UT Knoxville’s Forensic Anthropology Center, also known as the Body Farm.

A Body Farm is basically a big plot of land with a bunch of rotting corpses. It’s more formally known as a Forensic Anthropology Center. It’s a place for scientific research on human decomposition in a variety of settings. The research is ultimately applicable in forensic settings, i.e. to help solve murders n’ stuff.

When I worked there, I learned a ton of valuable skills that will really only come in handy if I or anyone else ever needs to hide a body.

Here are some of gross things I did, stated in the least-ish graphic way possible along with some “why I did that” type details.

The first thing you notice is the smell.

In the summer of 2013 I worked at UT Knoxville’s Forensic Anthropology Center, also known as the Body Farm.

A Body Farm is basically a big plot of land with a bunch of rotting corpses. It’s more formally known as a Forensic Anthropology Center. It’s a place for scientific research on human decomposition in a variety of settings. The research is ultimately applicable in forensic settings, i.e. to help solve murders n’ stuff.

When I worked there, I learned a ton of valuable skills that will really only come in handy if I or anyone else ever needs to hide a body.

Here are some of gross things I did, stated in the least-ish graphic way possible along with some “why I did that” type details.

THE SETUP

The Forensic Anthropology Center at UT Knoxville functioned in a pretty predictable fashion. First, somebody has to die. Even if you’ve generally donated your body to science, you probably won’t end up at the Body Farm. You have to sign up to donate years in advance. I often say, “people are dying to get in.” If the body has been specifically donated to the Body Farm, it goes there.

Once it arrives it goes through intake at an of-site location. We take pictures of the state of the body, hair and nail samples, and blood samples (which is often difficult because once the blood has been sitting for a while, it coagulates. I’ve had to jam a needle deep into someone’s carotid artery right in the soft part at the base of the neck). If there’s a spot for it to go out onto the body farm, we take it there. If not, it “chills” in the refrigerated section until there’s room at the farm.

Once the body is transported to the farm, it goes to a designated plot of land. It’s laid out in the dirt and most of the time, stays covered by a black plastic tarp (mostly to protect it from hungry animals). We photograph sections of the body once a day to document the process of decomposition. These variables are also subject to change depending on what type of research is being done (how a body decomposes after its embalmed, how a body decomposes after dismemberment, etc etc).

The corpse decays out in the open for a while until it reaches a certain level of dessication. At this point, the remains will take a long ass time to fully skeletonize if left out in the open. So we bury them.

The remains stay in the ground for a set amount of time to ensure they’re fully skeletonized, at which point they’re dug up. Then the bones are carefully catalogued, washed, and are transported to the skeletal collection (which is an insane place, located under the UT Knoxville football stadium). There they live...forever. The bones are used in different research studies and for teaching purposes.

THE NITTY GRITTY

The body farm was also a place where law enforcement and other forensic professions could go to learn stuff. I taught them about the varying stages of decomposition, how to properly identify grave sites, how to identify human remains, and how to dig up a body without destroying absolutely everything.

I stuck my hand into a human corpse that was full of maggots (to see how much heat was generated by maggots consuming rotting human flesh). I think this was some kind of hazing ritual.

I learned how to “break the rigor” from a body. During intake, most of the bodies that came in were...really stiff. Rigor mortis sets in super quickly and to be able to transfer a body, it needs to be un-stiff. So I got to...massage some dead bodies.

I dug a lot of graves and buried a lot of bodies.

I documented all of the stages of decomposition. I never destroyed anything but I did almost fall into one of the plots with a rotting corpse.

The next two things are pretty gross.

I call this story “Trashcans full of Torsos”

At one point we didn’t have any bodies that were dessicated enough to be buried, but we had an open grave. Serendipitiously, a grad student had conducted a study on decomposition after dismemberment. But had only used the heads and the limbs. The torsos were stored in some trash cans, out in the open in the hot Tennessee summer for a prolongued period of time. The other interns and I were instructed to put those remains in the grave. So, 2 other interns and I lugged the trashcans down to the grave site and poured the completely liquefied remains into the grave and buried them. And then we had to clean the trashcans...I took about 7 showers after that day.

I call this story “Bucket of Baby”

The Body Farm was located next door to a hospital. We often parked in the hospital parking lot and went there for lunch. Since it was so close, a lot of times people would try to give the remains of their loved ones to the Body Farm. They rarely accepted older individuals but what they did accept where deceased infants. Any kind of skeleton is useful for research, especially ones of children and infants because, and this sounds extremely callous but I don’t know how to put it otherwise, they were harder to come by.

Often times, families whose babies died in childbirth or were stillborn would choose to donate the remains to the Body Farm. Because the corpses were so delicate and the bones so small, they weren’t placed on the farm (mostly for fear of scavengers). Instead, the bodies were placed in a bucket of water where the flesh slowly separates from the bones. Every few weeks, the bucket would start to smell and we’d carefully pour the water out, sift through what we could to retrieve skeletal remains, and place what was still in-tact back in a bucket with fresh water to continue decaying. This process was done over many weeks until the full skeleton separated from the flesh at which point it was cleaned and transferred to the skeletal collection.

Since I’ve gone into a lot of detail about this process, all I’ll say is that I had to do it.

The Forensic Anthropology Center at UT Knoxville functioned in a pretty predictable fashion. First, somebody has to die. Even if you’ve generally donated your body to science, you probably won’t end up at the Body Farm. You have to sign up to donate years in advance. I often say, “people are dying to get in.” If the body has been specifically donated to the Body Farm, it goes there.

Once it arrives it goes through intake at an of-site location. We take pictures of the state of the body, hair and nail samples, and blood samples (which is often difficult because once the blood has been sitting for a while, it coagulates. I’ve had to jam a needle deep into someone’s carotid artery right in the soft part at the base of the neck). If there’s a spot for it to go out onto the body farm, we take it there. If not, it “chills” in the refrigerated section until there’s room at the farm.

Once the body is transported to the farm, it goes to a designated plot of land. It’s laid out in the dirt and most of the time, stays covered by a black plastic tarp (mostly to protect it from hungry animals). We photograph sections of the body once a day to document the process of decomposition. These variables are also subject to change depending on what type of research is being done (how a body decomposes after its embalmed, how a body decomposes after dismemberment, etc etc).

The corpse decays out in the open for a while until it reaches a certain level of dessication. At this point, the remains will take a long ass time to fully skeletonize if left out in the open. So we bury them.

The remains stay in the ground for a set amount of time to ensure they’re fully skeletonized, at which point they’re dug up. Then the bones are carefully catalogued, washed, and are transported to the skeletal collection (which is an insane place, located under the UT Knoxville football stadium). There they live...forever. The bones are used in different research studies and for teaching purposes.

THE NITTY GRITTY

The body farm was also a place where law enforcement and other forensic professions could go to learn stuff. I taught them about the varying stages of decomposition, how to properly identify grave sites, how to identify human remains, and how to dig up a body without destroying absolutely everything.

I stuck my hand into a human corpse that was full of maggots (to see how much heat was generated by maggots consuming rotting human flesh). I think this was some kind of hazing ritual.

I learned how to “break the rigor” from a body. During intake, most of the bodies that came in were...really stiff. Rigor mortis sets in super quickly and to be able to transfer a body, it needs to be un-stiff. So I got to...massage some dead bodies.

I dug a lot of graves and buried a lot of bodies.

I documented all of the stages of decomposition. I never destroyed anything but I did almost fall into one of the plots with a rotting corpse.

The next two things are pretty gross.

I call this story “Trashcans full of Torsos”

At one point we didn’t have any bodies that were dessicated enough to be buried, but we had an open grave. Serendipitiously, a grad student had conducted a study on decomposition after dismemberment. But had only used the heads and the limbs. The torsos were stored in some trash cans, out in the open in the hot Tennessee summer for a prolongued period of time. The other interns and I were instructed to put those remains in the grave. So, 2 other interns and I lugged the trashcans down to the grave site and poured the completely liquefied remains into the grave and buried them. And then we had to clean the trashcans...I took about 7 showers after that day.

I call this story “Bucket of Baby”

The Body Farm was located next door to a hospital. We often parked in the hospital parking lot and went there for lunch. Since it was so close, a lot of times people would try to give the remains of their loved ones to the Body Farm. They rarely accepted older individuals but what they did accept where deceased infants. Any kind of skeleton is useful for research, especially ones of children and infants because, and this sounds extremely callous but I don’t know how to put it otherwise, they were harder to come by.

Often times, families whose babies died in childbirth or were stillborn would choose to donate the remains to the Body Farm. Because the corpses were so delicate and the bones so small, they weren’t placed on the farm (mostly for fear of scavengers). Instead, the bodies were placed in a bucket of water where the flesh slowly separates from the bones. Every few weeks, the bucket would start to smell and we’d carefully pour the water out, sift through what we could to retrieve skeletal remains, and place what was still in-tact back in a bucket with fresh water to continue decaying. This process was done over many weeks until the full skeleton separated from the flesh at which point it was cleaned and transferred to the skeletal collection.

Since I’ve gone into a lot of detail about this process, all I’ll say is that I had to do it.